SGCI News

Food recipes developed from indigenous plants and adapted to local climates could improve nutrition and alleviate food shortages in rural households in Sub-Saharan Africa, researchers say. The African researchers created…

Food recipes developed from indigenous plants and adapted to local climates could improve nutrition and alleviate food shortages in rural households in Sub-Saharan Africa, researchers say.

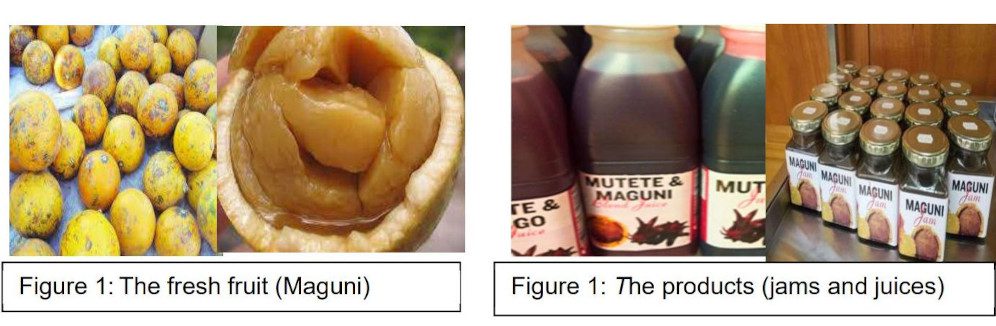

The African researchers created products – including jams, juices, syrups, yogurts, and instant soups – using plants such as wild orange, wild medlar, amaranthus, baobab, hibiscus, and violet tree.

Their recipes aim to address micronutrient deficiencies in the region and reduce post-harvest losses of indigenous fruits and vegetables, say the researchers from the University of Namibia and Mozambique’s Institute of Agricultural Research.

Penny Hiwilepo-van Hal, a co-author of the project and head of the Department of Food Science and Systems at the University of Namibia, said that since 2020 the team have been processing, upscaling, and commercialising food products derived from underutilised fruits and plants.

“The [project] seeks to provide the technical and market underpinnings for upscaling through the development of sustainable value chains and the successful commercialisation for these products,” Hiwilepo-van Hal said.

“We aim to solve the problems of inadequate scientific and technical data to establish and grow sustainable value chains for utilisation of indigenous fruit and vegetables and promote commercialisation,” she explained.

The research was funded by the Science Granting Councils Initiative (SGCI) and coordinated by the Science Granting Councils of Namibia and Mozambique – Namibia’s National Commission on Research, Science and Technology and Mozambique’s National Research Fund.

Chinemba Samundengu, co-researcher and lecturer at the University of Namibia’s Department of Food Science and Technology, believes developing indigenous food products can help popularise underused foods.

“Increased utilisation of these indigenous fruits and vegetables through product development can lead to increased demand and market access,” said Samundengu.

“This would serve as a motivation for development of the value chains from these indigenous species.”

Health, climate benefits

Hiwilepo-van Hal said the research team targeted plant species with specific health benefits, including those that “enhance immunity, reduce the risk of micronutrient deficiencies, infertility, and cancers”.

“[For] violet tree, theleaves could be used in human nutrition to reduce haemoglobin and infertility deficiencies while inhibiting the development of chronic diseases through the effect of plant antioxidants,” she explained.

Preliminary cytotoxicity tests – which show the extent of damage a substance can do to cells – indicated that at high concentrations extracts of the violet leaf could potentially be used against human cells such as cancer cells, [but] more detailed cytotoxicity and phytochemical analysis is needed, added the researcher.

She also believes that the promotion and uptake of nutritious, indigenous plants and fruits will be helpful in the development of climate-resilient food systems.

“This will help ensure sustainable access to affordable micronutrients in vulnerable rural households,” she added.

“Current variations in weather patterns have proved to be very disruptive to food systems in Africa, severely impacting food security.”

Daniel Otaye, an associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Egerton University in Kenya, says the research is promising, but more studies need to be done on sustainability and wide-scale commercialisation of the indigenous plant products.

“Africa is struggling with numerous challenges including climate change and food security, the findings of this study can help solve some of these challenges,” he said.

SGCI is a multilateral initiative established to strengthen the institutional capacities of public science funding agencies in Sub-Saharan Africa to support research and evidence-based policies that will contribute to economic and social development.

Article written by Nelson Mandela Ogema

Related News

Building Africa’s science future: inside the SGCI alliance

As Phase 3 of the Science Granting Councils Initiative launches on the margins of the African Union Summit in Addis Ababa last week, the SGCI Alliance Chair explains why this moment marks a decisive turning point for African science. Cephas Adjei Mensah describes what is…

Open call: Support for science granting councils in Sub-Saharan Africa

The International Development Research Centre (IDRC), through the Science Granting Councils Initiative (SGCI), has launched a call for proposals to support science granting councils in Sub-Saharan Africa in the establishment and operationalisation of the Capacity Strengthening Hub under Phase III of the SGCI-3. The Hub…

SGCI phase 3: USD 42M boost for Africa’s STI agenda

It was an exhilarating moment as the Science Granting Councils Initiative (SGCI) Phase 3 funding announcement was officially made yesterday during the Science, Technology, and Innovation (STI) Week 2026, held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The STI Week, organised by AUDA-NEPAD and the African Union and…

SGCI funded projects

Rwanda’s integrated approach to sustainable agriculture and nutrition

Project Titles & Institution Areas of Research Number of Projects being funded Project Duration Grant Amount In-Kind Distribution Council Collaboration with other councils