SGCI News

When policy-makers and strategic planners gather to talk about addressing gender and inclusivity issues in research, the predominant focus tends to be on how to bring more women into the…

When policy-makers and strategic planners gather to talk about addressing gender and inclusivity issues in research, the predominant focus tends to be on how to bring more women into the existing science, technology and innovation system through the implementation of strategies such as quotas and mentoring programmes.

The absence of women is framed as a deficit or gap that needs to be filled.

But what if the system itself also needs to change? What if the conventional understanding of knowledge needs to be broadened to include different ways of knowing that new participants in the system might bring?

These were some of the issues raised during an online feminar held in July 2022 facilitated by Gender at Work as part of their Gender Action Learning process for the HSRC Gender & Inclusivity Project aimed at advancing gender and inclusivity within science granting councils in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Co-creation of knowledge

Gender at Work associate and feminar chair Nina Benjamin said facilitators of the session sought to foreground the concept of co-creation. “This is no group of experts come to speak on a topic; it’s about bringing ideas together to co-create a process.”

Guided by the question, “What does it take for Science Granting Councils to support research that values different ways of knowing”, the Gender at Work team led a conversation that probed fundamental anomalies, such as why best practices and innovation, achieved over generations in traditional communities and particularly by women, are not recognised as “scientific” even though such work is the product of careful long-term observation, testing and fine-tuning.

A short video at the start of the feminar about a gender action learning (GAL) project funded by Oxfam and conducted in a rural area of Chiure in north-eastern Mozambique framed important issues relating to the value of contextualisation and integration of disciplines and knowledge forms in research.

In the video, women farmers were invited to participate in a life-changing innovation: the development of a hoe specifically designed for women.

The process successfully produced a tool that was sharper, lighter and had a longer handle – all of which had the effect of reducing excessive strain on the body of its female user, and raising productivity.

But the project outcomes extended far beyond the production of the new hoe: as part of the project, the women acquired skills in basic marketplace financial exchanges, informal savings schemes, and they were challenged to re-think the traditional gender roles that operated in their households which handed most of the decision-making responsibilities to men and left women to bear the brunt of domestic work.

Importantly, the women’s male partners were also shown to benefit from the programme’s consciousness-raising approach and both male and female participants reported significant shifts in the gendered division of labour in their households.

As highlighted by Gender at Work senior associate Michal Friedman, the Hoe Project offered valuable lessons for anyone aiming to translate the concept of integration and sensitivity to context into action.

“That video shows something about how the process of doing research is linked to how the end result is to be used”.

“All the stakeholders actively connected to the issue are participating in such a way that all voices are heard,” she said. “This requires a whole different way of doing things. It’s a profound challenge … one that is harder than getting more women into the loop.”

Privileged knowledge

Thus, the video provided an opportunity for researchers to reflect on their own work and moved the discussion beyond quotas and quantitative outcomes towards a radical interrogation of the way in which funding decisions were made by councils. As Benjamin put it: “Whose knowledge is privileged … and, more importantly, who is this knowledge for and how is it created?”

By any standards, it is a complex question but one that was crystallised through the example of Veronica Bekoe, a biological scientist from Ghana who invented the Veronica Bucket, a device for hand washing that reduces the spread of communicable diseases and proved to be particularly valuable during COVID-19. Despite the bucket being widely used in Ghana and neighbouring countries, Bekoe has up until today been unable to formally patent the bucket system.

According to independent consultant Eleanor du Plooy, Bekoe’s story underscores the reality that women often do not receive formal recognition for their innovations, particularly if such innovation is perceived to be oriented towards caregiving or having a distinctly social, as opposed to monetary, impact – an argument that resonated with comments made earlier by Friedman about the dangers of binarism that comes from elevating commodification above societies.

“Bekoe was more concerned with identifying a critical need and solving a problem than making money, said Du Plooy, “which leads us to ask: what types of technology are sufficient to be considered innovative rather than rudimentary? And how are decisions made about funding those innovations? What criteria and values are used?

Echoing these ideas, Khanyisa Mabyeka, a gender and development consultant currently based in Berlin, argued that although women are traditionally regarded in many African communities as the custodians of seeds and have extensive expertise in their selection, planting and storage – indigenous knowledge that is vital to the wellbeing of the community – none of this “knowing” is regarded as “scientific”, despite being gained over years of careful observation and testing.

Valuing existing knowledge

Challenging councils to find ways to “value the knowledge that is already there”, Mabyeka noted that women seed custodians had been “studying” their discipline for much longer than researchers with PhDs.

“How do we value that knowledge within our science council system? How do we acknowledge that they already have knowledge and skills and … there is something in the system that is not allowing them to shine? What would have to change in those systems for all of those people to be able to flourish and access the resources councils are making available?”

Critiquing the notion that (western) scientific methods and reason, which exist outside of an individual historical and social context, are “the only reliable sources of objective knowledge that can provide humanity with universal truths”, senior research specialist at AISA-HSRC Olga Bialostocka said that what is considered to be evidence often depends on context.

“What exists and how we know it exists is linked to a person’s philosophical stance, their ontology and their epistemology. Hence, what kind of evidence can be accepted as true or objective is in a sense a subjective matter,” she said.

Calling for a continuation of the conversation between the hard sciences and humanities, Bialostocka said: “If we acknowledge there are many ways of knowing and alternative visions of society, evidence-based research cannot be reduced to purely scientific knowledge the way it is defined through western concepts, but needs to explore ways other people make sense of their lives using different epistemologies, how they understand the connection between the material and spiritual, the tangible and the intangible. It also requires recognising alternative ethics for human conduct.

A conversation between hard sciences and humanities

“The conversation between hard sciences and humanities needs to continue so that humankind can flourish irrespective of context and creativity be recognised regardless of origins.”

Asked how councils might respond if approached to fund a project like that of the Hoe Project – one that is technologically innovative and conducted in contextually specific and integrated way – Tafsir Babacar, representing the directorate in charge of financing research and technological development in Senegal (DFRSDT), responded by saying while his country’s government had made provision for gender equality and representivity at a political level, inequality was still evident in research programmes owing to the way in which society is structured.

“[Women] have the same skills and knowledge [as men] but when they start a research project, they are often unable to complete the project on time owing to family responsibilities,” he told the feminar.

He said there were instances where women were given more time to complete their PhDs and projects are being targeting specifically at women.

“We are considering these issues, and trying to see … when we call for project proposals, how we can favour those projects that are helpful to women and put them on par with men.”

Re-thinking criteria

Rudo Tamangani of the Research Council of Zimbabwe proposed a “rethinking” of the criteria used by science granting councils for the granting of project funds. She said indigenous knowledge system-based research was currently “out of our purview because the criteria we use do not support that type of research”.

However, she said there was a need to rethink existing criteria in terms of supporting research and what was deemed to be innovation.

“For example, the Veronica Bucket is not strictly a new invention but new in a sense that it is serving a need and at that level, we can recognise the innovation that has gone on,” she said.

Speaking from Burkina Faso, Aminata Kabore said the country’s science granting council takes into account women and men who have knowledge that is not academic by sending two calls for proposals, one of which is aimed at innovators outside of the mainstream research system. “It’s a lighter process to enable these people to share proposals and show what they can do and include their knowledge in development,” she said.

Training sessions are offered to selected participants and the focus is on method rather than methodology.

“We have this in place to have them tell us what they can do and to integrate indigenous knowledge into the conventional system.”

* The second Gender At Work Feminar focused on Artificial Intelligence was held on 20 September 2022.

Author: Jive Media Africa

Related News

Namibia launches national research infrastructure survey report

The Namibia National Commission on Research, Science and Technology has officially launched the country’s Research Infrastructure Survey Report, outlining existing research facilities, key gaps, and priority areas for development. The report was presented on 3 March at the Franco-Namibian Cultural Centre in Windhoek before an…

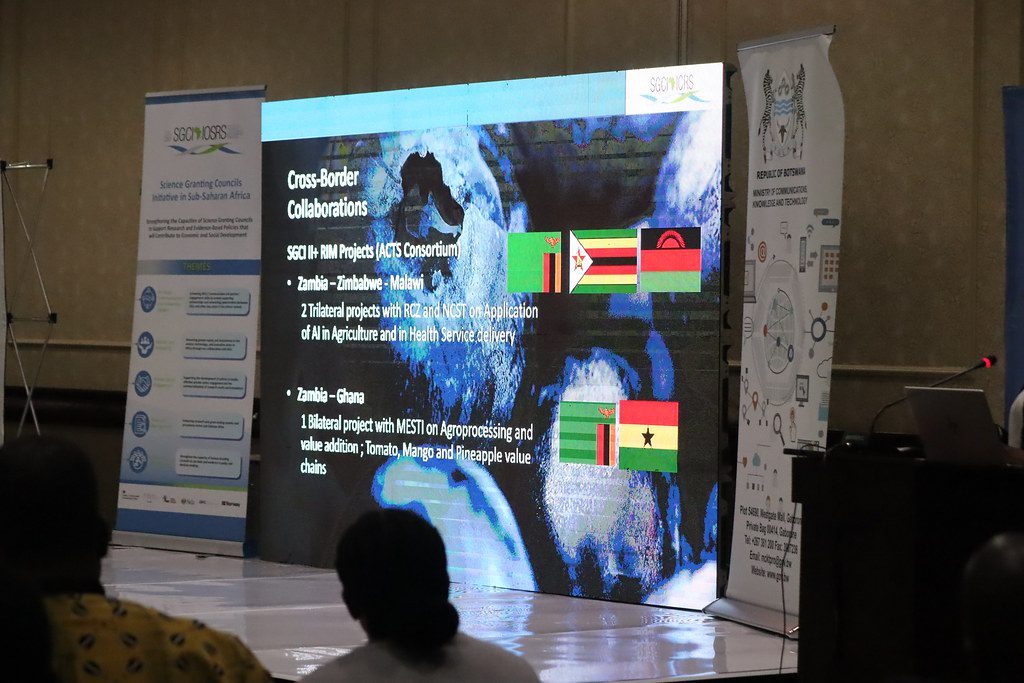

How Zambia’s science council is funding research that matters

When Zambia’s National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) was established in 1997, its founding vision was to harness science, technology, and innovation to improve the lives of ordinary Zambians. More than two decades later, that vision is increasingly taking shape through a growing portfolio of…

Voices of SGCI: Council leaders on the direction and ambition of SGCI 3

At the African Union’s Science, Technology and Innovation Week in Addis Ababa, earlier this month, leaders of science granting councils reflected on what SGCI Phase 3 represents for Africa’s science and innovation systems. From ownership and alignment to stewardship and sustainability, here are their voices…

SGCI funded projects

Rwanda’s integrated approach to sustainable agriculture and nutrition

Project Titles & Institution Areas of Research Number of Projects being funded Project Duration Grant Amount In-Kind Distribution Council Collaboration with other councils