SGCI News

A new webinar series on gender equality and inclusivity in research funding draws on the conviction that research that is informed by a gender equality and inclusion lens offers the…

A new webinar series on gender equality and inclusivity in research funding draws on the conviction that research that is informed by a gender equality and inclusion lens offers the best chance the world has of meeting its sustainable development targets.

In almost any discussion of gender equality and empowerment of women and girls, the following questions invariably emerge: “Are we going too far? In our attempts to right a wrong, are we giving undue advantage to women and girls to the exclusion of men and boys?”

For Dr Jemimah Njuki, chief of economic empowerment at UN Women, it’s an emphatic no.

One of three panellists in a webinar hosted last week by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) to discuss the merits of a gendered lens in research funding, Njuki fell back on science: “We are not at the point where women have undue advantage. All our data tells us that.”

While stressing the need to engage men and boys in gender-related issues because “gender equality is good for everybody”, she added: “We are not yet at the stage where girls everywhere are leading the lives they dream of and aspire to”.

Njuki’s comments, particularly about what the data say, are backed up by a recent warning from a United Nations sustainability progress report which warns the continued failure by the global community to prioritise SDG 5 (gender equality) will imperil the entire 2030 Agenda.

“Halfway to 2030, the world is failing women and girls,” notes the report, Progress on the sustainable development goals: The Gender Snapshot 2023. “Globally, no SDG 5 (Gender Equity) indicator is at the ‘target met or almost met’ level,” it states. “A continued failure to prioritize SDG 5 will put the entire 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in peril.”

That worrying pushback, and the UN’s warnings about a lack of progress, are serving to galvanise the ongoing efforts of African academics and researchers, including those in the HSRC in South Africa who are working to mainstream gender equality and inclusivity (GEI) by focusing on the research funding cycle as a means to draw more women, at more points, into the research ecosystem.

And instead of a global trajectory towards gender parity, some countries are witnessing instances of active “pushback” against gender and inclusivity initiatives and the rolling back of women’s rights, including health and reproductive rights, Njuki noted.

This important work is being done within the ambit of the Gender Equity and Inclusivity Project of the Science Granting Council’s Initiative (SGCI), currently being implemented by the HSRC, non-governmental organisation Portia, and Jive Media Africa.

Thirteen African science granting councils are currently involved in the project which is driven by the understanding that research funding that adopts a GEI lens – also accounting for how different forms of inequality intersect – can enhance the rigour, contextual relevance and social benefit of research.

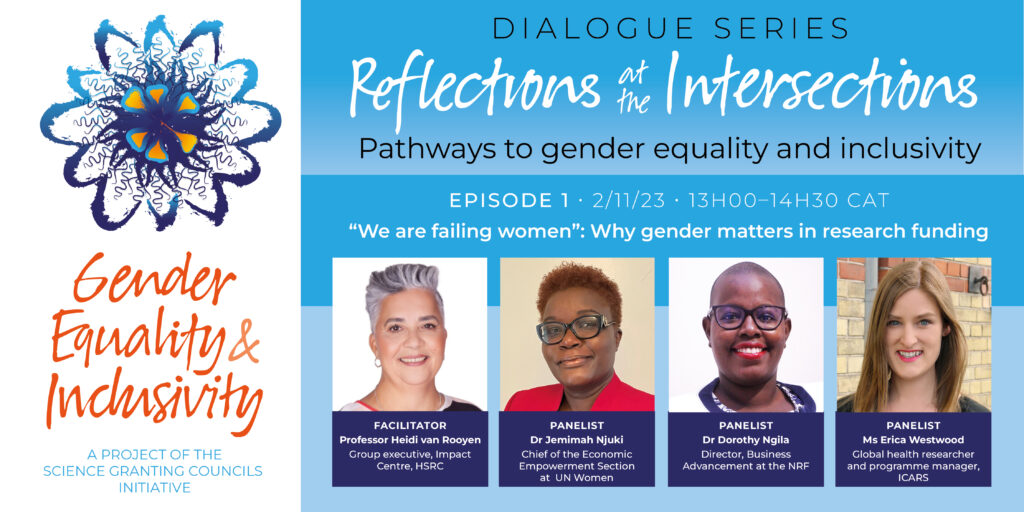

It also “offers the best chance we have at meeting sustainable development targets,” according to Prof Heidi van Rooyen, head of the HSRC Impact Centre, who facilitated this webinar, which is the first of a series entitled “Reflections at the Intersections”, which was conceived as a forum to share insights into gender transformation initiatives and practices in various organisational contexts – all of which are aimed at helping to encourage gender transformation efforts more broadly.

The inaugural webinar held on 2 November 2023, aimed to explore why a gendered lens was needed in research – and why now.

Njuki was joined on the panel by Dr Dorothy Ngila, director of business advancement at the South African National Research Council, and Erica Westwood, implementation research advisor for the International Centre for Antimicrobial Resistance Solutions (ICARS).

Both panellists joined Njuki in emphasising the importance of hard data and scientific evidence in challenging the pushback against gender equality and inclusivity by putting data in front of governments which shows the full extent and nature of the problem. This is a particular challenge in developing countries where sex and gender-disaggregated data is often unavailable.

“There’s a lot of descriptive work”, Njuki said “I see it in universities and among students, but what we see less of is an analysis of cause and effect. It’s very important to start going deeper. If there’s a gender pay gap, for example, we need to know about the gap, but also why it exists, what the causes are [and how it can be addressed]. This kind of analysis will help governments to prioritise.”

She also stressed the need for a gender lens to apply to all research fields, including new emerging areas of research such, as AI and information technology.

Tackling questions about how to bring an appreciation of intersectionality (the overlapping of several social identities, often also the locus of discrimination) into research work, Westwood admitted the concept can be “daunting for researchers”, particularly those coming from disciplines outside of the humanities and social sciences. But understanding intersectionality was closely related to sensitivity to and understanding of context.

“It is impossible not to recognise these challenges if you want to understand the issues that organisations are working with and the contexts in which they are working. We have to go back and understand who the people are and the context we are in,” she told the webinar.

She stressed that having the right data and information was a critical starting point from which to “push further into intersectionality and learn from other areas that have done this well”.

One of these areas is HIV research. “If you look at the HIV space, I don’t think that until gender and intersectionality were brought forward did we see global progress [in treatment and prevention strategies]. Westwood also referenced the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, arguing that it was not until cultural practices among populations at risk were more deeply examined that scientists started to harness that understanding and develop more effective preventative measures to deal with what were essentially regional and global challenges.

Ngila, who described the role of public funding agencies such as the one she represents as “catalytic” in fostering the kind of research ecosystem needed to contribute towards meeting SDG goals, briefly set out the comprehensive series of initiatives taken by the NRF to improve the representation of women in research.

Ngila said advocacy skills, technical competence and access to solid data and evidence constituted an effective combination when it came to convincing decision-makers and leaders of the merits of gender equality and inclusivity initiatives.

She said gender equality and inclusivity “cut across all SDGs, so prioritisation is a question of how we deepen our work across all of them and that comes back to ensuring we have the data and evidence. It comes back to the question: how am I contributing to fixing the [research] system, the numbers [lack of representation among women] and the science [what kind of research is being done] in each of the different SDGs?”

Ngila also spoke of the need to build a human capital development pipeline for research – supporting undergraduate students to stay in the higher education and research system, but also making “high-end investments” in the form of centres of excellence and research chairs.

At a basic level, too, she said there was a need to strengthen the capacity of researchers in terms of the methodologies needed to apply sex and gender as units of analysis.

The issue of capacity was raised by the other panellists. Njuki made the point that people were unlikely to pursue a gender lens in research if they did not have the capacity to do so if there was no learning available, and if there was no sharing of best practices – a series of points that highlighted the value of both the GEI project and its recently launched webinar series.

For more information see the SGCI GEI project here.

To stay updated regarding the next webinar, subscribe to the HSRC newsletter.

A recording of the webinar can be found here.

The SGCI GEI Project is led by Dr Ingrid Lynch (PI) in the HSRC’s Public Health, Societies and Belonging (PHSB) Division and Prof Heidi van Rooyen (co-PI) in the HSRC Impact Centre.

Related News

Namibia launches national research infrastructure survey report

The Namibia National Commission on Research, Science and Technology has officially launched the country’s Research Infrastructure Survey Report, outlining existing research facilities, key gaps, and priority areas for development. The report was presented on 3 March at the Franco-Namibian Cultural Centre in Windhoek before an…

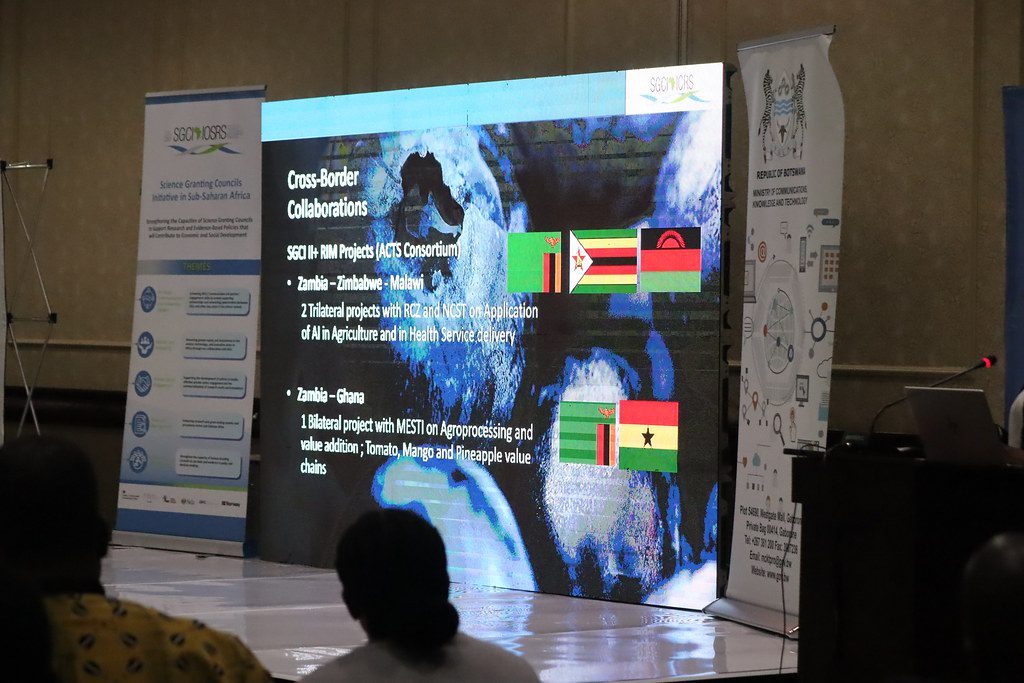

How Zambia’s science council is funding research that matters

When Zambia’s National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) was established in 1997, its founding vision was to harness science, technology, and innovation to improve the lives of ordinary Zambians. More than two decades later, that vision is increasingly taking shape through a growing portfolio of…

Voices of SGCI: Council leaders on the direction and ambition of SGCI 3

At the African Union’s Science, Technology and Innovation Week in Addis Ababa, earlier this month, leaders of science granting councils reflected on what SGCI Phase 3 represents for Africa’s science and innovation systems. From ownership and alignment to stewardship and sustainability, here are their voices…

SGCI funded projects

Rwanda’s integrated approach to sustainable agriculture and nutrition

Project Titles & Institution Areas of Research Number of Projects being funded Project Duration Grant Amount In-Kind Distribution Council Collaboration with other councils